Sobre construcción abierta, auto-construcción y auto-organización

Tras varios siglos en los que los modos de construcción que fueron totalmente comunes y normales prácticamente en cualquier lugar [...]

14 agosto, 2017

por Adam Greenfield

After a few centuries during which the modes of construction that had been completely unremarkable and normal practice virtually everywhere on Earth were broadly eclipsed by professionalization, we once again find ourselves living in an era in which ordinary people might venture to build the structures they live, work and dream in.

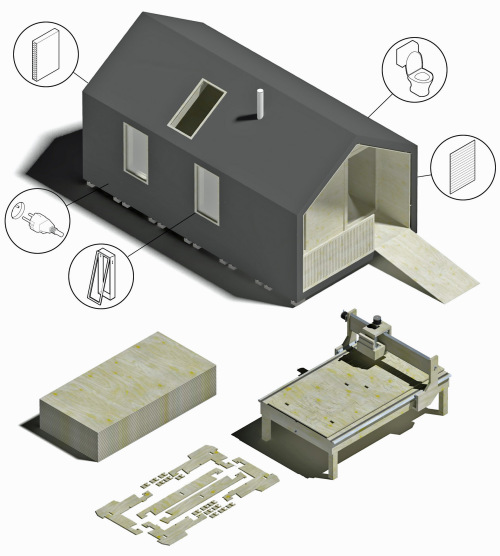

Those paying more than casual attention to the field can most likely think of half a dozen such schemes, of varying degrees of intellectual and aesthetic resolution, with names like the Global Village Construction Set, Kiosk 2.0, prodUSER and Transparent Tools. Despite the relatively advanced and expensive technology at their core, many of these systems seem to have been devised originally with a particular scenario in mind: the low-cost provision of self-built housing and services in and by informal communities of the global South.

But can these principles work as well in the developed North, where it’s material that tends to be cheap, and labor expensive? Or is it just the other way around: does the success of open-source construction absolutely require the installed technical base so relatively easy to locate in the developed world, and so very challenging to avail ourselves of elsewhere?

I was lucky enough to put all these questions to the test. My partner and I were invited to Rugby on a sunny Sunday in the late summer of 2015, to help with the raising of a WikiHouse structure. We got an intimate look at the benefits and disadvantages of this way of thinking, building and dwelling, and I’d like to share with you some of my reflections on the experience. Some of the observations that follow are specific to WikiHouse. My intention, though, is to say something more broadly regarding attempts to found real-world amateur construction on a distributed and freely-licensed digital infrastructure.

The tyranny of structurelessness (when raising a structure)

As intended for this test build, most of the fifteen-odd people on site had no significant previous experience of construction or building; the intelligence, as it were, resided in the thousand or so components themselves, painstakingly devised and milled. All we had to do was hammer them together with the provided mallets, according to instructions only a little more complicated than those that accompany any flat-pack Ikea or Muji furniture. But first we had to figure out how to work as a group — a random assortment of people, few of whom knew each other at the start of the day.

Calling on a ramified, complex ecosystem of parts, and involving different kinds and scales of tasks, the process of building a WikiHouse had an interesting relationship to the typical pitfalls that can often arise in flat groups, where roles and titles and all the other trappings of formal hierarchy simply aren’t there to call upon. There were still occasions for frustration with the difficult process of achieving consensus, but there was also always something useful to do, even for people who’ve decided that they need to go off and work on their own for awhile.

Coiled up in the long tail

Since its components need to be precision-cut by a yard equipped with the necessary CNC milling machine, WikiHouse implicitly depends on the existence and accessibility of a relatively high-technology infrastructure close to the construction site — either that, or the long-distance logistical infrastructure capable of delivering all of the required components to a potentially remote site.

I’ve already noted that a single, not-overly-large WikiHouse building requires something on the order of a thousand components, each of which must be milled from a sheet of plywood. Think of the demand this heavy utilization imposes on a fabrication facility — and especially compare this time burden to production techniques based on the ready (and incremental) availability of generic materials like bricks, 2x4s, aluminum sheeting or poured cement — and we can see that WikiHouse would only able to fulfill its promise were CNC milling machines as widely distributed as lumberyards are now. This is by no means an impossible circumstance to imagine, but we’re not there yet —neither here in the developed North, nor anywhere else on Earth.

Poor is the one who depends on the permission of another

A decent amount of friction arises, as well, where the idealism of open-source construction brushes up again the institutionalized practices of building in a formalized culture. Though WikiHouse was designed to exceed standard tolerances for structural integrity, the local bureaucrats responsible for approving the raising of new structures in Rugby, encountering something profoundly unfamiliar to them, evidently insisted on modifications before the plans could be certified.

Specifically, these modifications involved manually drilling a grid of holes into each of the cross-bracing members, and reinforcing the structure by screwing them together; given that waiting for a stock of prepared components to build up constituted the main bottleneck in the flow of effort, I’m not sure I can fairly judge WikiHouse on its claimed speed of construction. It certainly would have gone more swiftly had we not been required to undertake this step. (I will say, too, that there is an acute irony in pencilling a grid onto precision-milled plywood pieces and then hand-drilling them, with a fraction of the speed and accuracy a numerically-controlled tool would have brought to the task.)

Challenges like this are bound to arise whenever something like WikiHouse is used in a culture where a robust building code exists, and is robustly enforced. I can easily imagine open-source techniques working well in places like rural Finland, where people build lake houses on their own all the time, sans permit or oversight. But otherwise it will be necessary to accommodate the culture of bureaucratic approval, perhaps by building up a stock of plans that are preapproved and certified for execution in a given jurisdiction.

Cornerstone principles

Finally, what I regard as the most important lesson I learned from our day with WikiHouse had to do with what might be thought of as the social protocol surrounding the act of construction.

Communal as it was, this act of construction felt displaced from the folkways that used to govern such efforts just about everywhere: the rituals that mark the inception of a shared investment of energy and effort in the raising of a structure, and upon completion consecrate it for dwelling and use.

It may be a terrible cliché to invoke the Amish barn-raising, with its dedication to not merely collective but mutual purpose, but that spirit was something I felt was missed in Rugby. Perhaps all WikiHouse plans could include a literal cornerstone element, to be inscribed with the names of everyone who worked on a raising. This is a small detail, but a telling one. We’ve done things like this to recognize those involved in the collective effort of building since there were buildings, and it feels absolutely vital to me to observe such formalities if we’re ever to profit from the binding of information-technological method into our lifeways of long standing.

Putting the pieces together

I remain convinced that a mature open building framework can and will allow small groups of untrained nonspecialists to build useful, ecologically sound structures themselves, quickly, at relatively low cost and with a minimum of energy and waste. I hugely applaud the time, energy and creative ingenuity being invested in their design and testing.

Experience suggests, however, that lavishing attention on questions of design can easily be a distraction and a trap — a way of avoiding difficult but important conversations, and not demanding the changes that really need to happen.

However innovative or resource-efficient it might be, the architectural design or engineering of a housing unit is less important than the fact that it is budgeted for, authorized and actually built in the first place. More: that it is thereafter occupied by the people most acutely in need of housing, and not simply delivered to the market as an investment vehicle.

These, clearly, are questions properly beyond the ambit of WikiHouse, as they are beyond the ambit of any set of procedures for the physical production of space. But a canny designer can nonetheless anticipate them, and take practical steps to prepare for the way in which system meets world. We can best think of open-source construction frameworks as part of a grand ecology of commoning systems still aborning, that in its maturity would necessarily include social practices and conventions alongside technologies and production procedures. Those of us concerned to see that housing is provisioned with principles of equity and justice foremost in mind should never make the mistake, though, of thinking that any such scheme can ever be sufficient in itself.

Tras varios siglos en los que los modos de construcción que fueron totalmente comunes y normales prácticamente en cualquier lugar [...]